12 Proportions

Let’s look specifically at proportions-type inference setups, where we apply a binomial model to sample proportions to infer about an underlying probability in the population. We will divide this into two scenarios:

- One-proportion scenario, where there is a single population with a single probability parameter of interest, and

- Two-proportions scenario, where there are two populations, each with its own probability parameter, which we seek to compare.

A proportions-type inference approach using a binomial model is only appropriate if your sample consists of either 1 or 2 samples where, for each sample, your data looks like counts across two categories, one of which we consider “success” and the other “failure” (e.g. heads/tails, true/false, etc.).

In these setups, the probability parameter of the binomial model always corresponds to the probability of the success category by convention. Make sure to define the category whose probability is of primary interest as “success”.

12.1 One proportion

12.1.1 Model notation

In the one-proportion scenario, suppose we draw a fixed sample size of \(n\) observations, each of which we model as independent and having some constant underlying true probability \(p\) of being a success, and \(1-p\) of being a failure (and there’s no other possible outcome).

It’s customary to use upper-case \(X\) to represent our model of the true distribution of \(x\), which here we choose to be \(X\sim\bin(n,p)\).

Let lower-case \(x\) be the observed number of successes in our sample, and note that we must have \(0\le x\le n\). Let \(\hat p=x/n\) denote then the proportion of successes in our sample.

Under these assumptions, \(\hat p\) is a natural point estimate for \(p\), i.e. our sample proportion of successes estimates the true underlying probability of success \(p\), since the LLN guarantees \(\hat p\to p\) as \(n\to\infty\).

Note several things:

- \(n\) must be a fixed, predetermined sample size,

- trials must be able to be reasonably modeled as independent,

- there must only be 2 possible outcomes (success & failure) for each trial,

- \(p\) is always the TRUE probability of the “success” category, however it’s defined,

- \(\hat p\) is the observed sample proportion, which can estimate the true \(p\) by LLN,

- \(X\) represents the theoretical RV model we choose to apply to the sample’s observed \(x\),

- \(x\) represents the actual observed number of successes in your sample out of \(n\) trials.

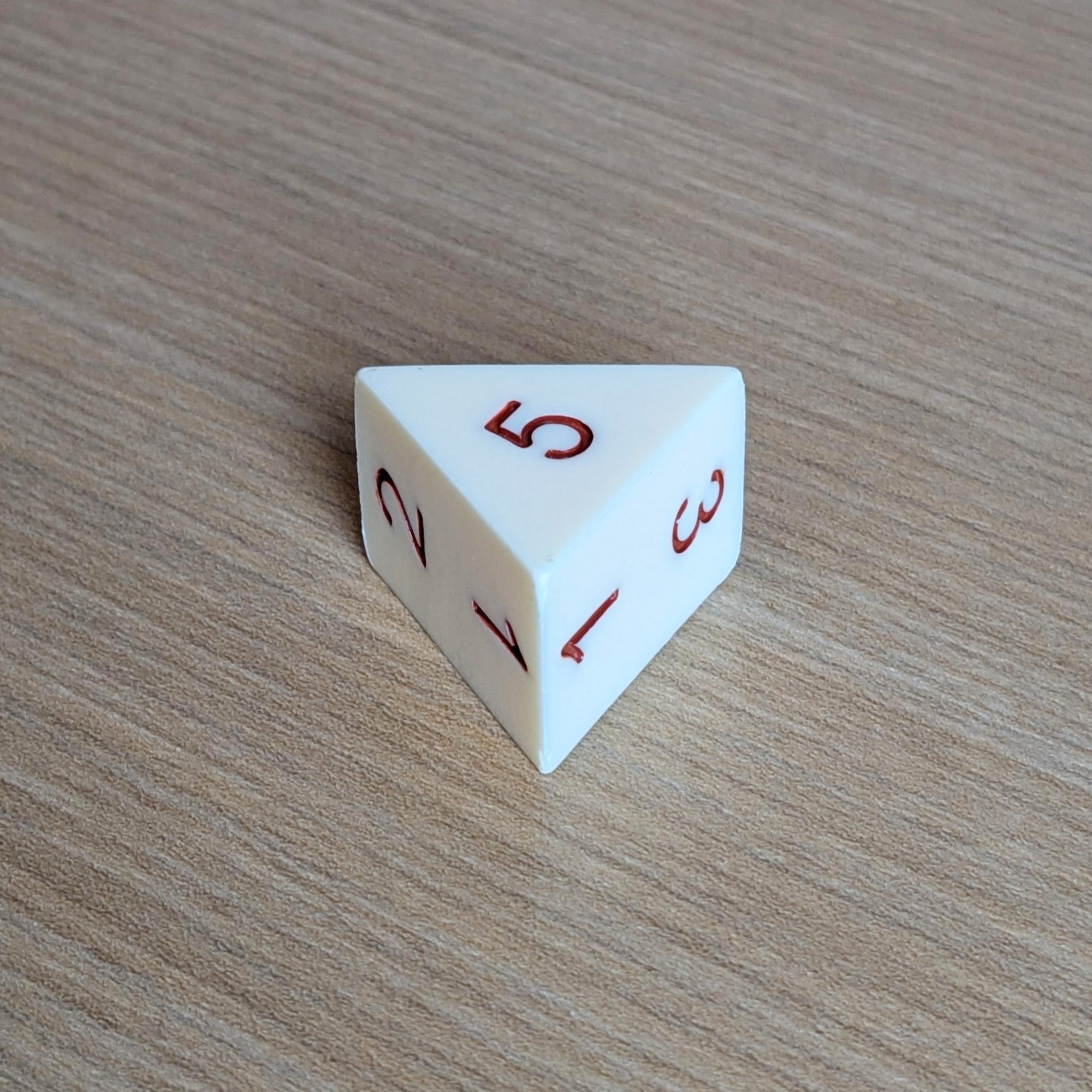

Let’s see all this in the context of an example. Below are \(n=200\) rolls of a purportedly fair 5-sided die I bought online (yes, I really sat in my office and rolled it 200 times).

# combine 50-roll chunks of data, split, then parse to numeric vector

rolls <- paste0("21252134521555355115322514314333142113433335345333",

"43242443535423223523352541521331244241531554241354",

"34244524112155254341541335443433245314125431131335",

"43114331251421521112234535251142334354341123345541") %>%

strsplit("") %>% unlist %>% as.numeric

rolls [1] 2 1 2 5 2 1 3 4 5 2 1 5 5 5 3 5 5 1 1 5 3 2 2 5 1 4 3 1 4 3 3 3 1 4 2 1 1

[38] 3 4 3 3 3 3 5 3 4 5 3 3 3 4 3 2 4 2 4 4 3 5 3 5 4 2 3 2 2 3 5 2 3 3 5 2 5

[75] 4 1 5 2 1 3 3 1 2 4 4 2 4 1 5 3 1 5 5 4 2 4 1 3 5 4 3 4 2 4 4 5 2 4 1 1 2

[112] 1 5 5 2 5 4 3 4 1 5 4 1 3 3 5 4 4 3 4 3 3 2 4 5 3 1 4 1 2 5 4 3 1 1 3 1 3

[149] 3 5 4 3 1 1 4 3 3 1 2 5 1 4 2 1 5 2 1 1 1 2 2 3 4 5 3 5 2 5 1 1 4 2 3 3 4

[186] 3 5 4 3 4 1 1 2 3 3 4 5 5 4 1

# quick table + bar plot of results using base R

table(rolls)rolls

1 2 3 4 5

39 32 50 41 38 Suppose my question of interest is whether this specific die design is in fact fair. There are different ways of testing this41, but a simple way using a proportions-type setup is to ask whether the two triangular-shaped faces (which are 4 and 5) are observed 2/5 or 40% of the time.

In this setup, we can define “success” as getting 4 or 5, which has theoretical probability \(p=0.4\). Our RV model for \(X\), i.e. the number of successes (4s & 5s), is then \(X\sim\bin(200,0.4)\).

In our sample, we observed \(x=41+38=79\) times this actually occurred, which gives us a sample proportion of \(\hat p=x/n=79/200=0.395\).

12.1.2 Confidence interval

For a one-proportion scenario, the confidence interval has the following form:

\[ \text{$C\%$ or $(1\!-\!\alpha)$ interval}~=~\hat p~\pm~z_{\alpha/2}\cdot\sqrt{\frac{\hat p(1-\hat p)}{n}},~\text{ where} \]

\(\alpha\) is implicitly defined as 100% – C%, e.g. for a 95% confidence interval, \(\alpha=1-0.95=0.05\),

\(\hat p=x/n\), the sample proportion of successes, is the point estimate for the true probability \(p\),

-

\(z_{\alpha/2}\) is the \(\alpha\)-level normal critical value such that \(\p(|Z|>|z_{\alpha/2}|)=\p(Z>z_{\alpha/2})+\p(Z<-z_{\alpha/2})=\alpha\), in other words the observation on the standard normal such that the two “outer-tails” defined by it and its mirror image sum to \(\alpha\) together.

library(latex2exp) ggplot() + geom_function(fun=dnorm, xlim=c(-4,4)) + stat_function(fun=dnorm, geom="area", xlim=c(-4,qnorm(.025)), fill="red") + stat_function(fun=dnorm, geom="area", xlim=c(qnorm(.975),4), fill="red") + scale_x_continuous(breaks=qnorm(c(.025,.5,.975)), minor_breaks=NULL, expand=0, labels=TeX(c("$-z_{\\alpha/2}$","0","$z_{\\alpha/2}$"))) + scale_y_continuous(breaks=NULL, limits=c(0,.4), expand=0) + theme(axis.text.x=element_text(size=13)) + labs(x=NULL, y=NULL, title=TeX("$z_{\\alpha/2}$ critical value for Z (red areas sum to $\\alpha$)"))This value is called \(z_{\alpha/2}\) since by convention the subscript denotes the area of only the right-corner, which is \(\alpha/2\) by symmetry. To compute \(\alpha/2\) for a C% interval, you need to ask

qnorm()for the \((1-\alpha/2)\)–percentile, e.g. for a 95% confidence interval, we seek the 97.5%-tile:# for a given α, e.g. alpha <- 0.05 # compute the 1-α/2 percentile as the z_α/2 critical value 1-alpha/2[1] 0.975qnorm(0.975) # often approximated as 1.96 or simply 2[1] 1.959964 and finally \(\se(\hat p)=\sqrt{\hat p(1-\hat p)/n}\) is the estimated standard error of \(\hat p\), which can be thought of as dividing the binomial SD by \(n\) then substituting \(p\to\hat p\) everywhere.

Continuing the example above, a 95% confidence interval for \(p\) based on 79 successes out of 200 trials can be computed as:

[1] 79

n[1] 200

# define p-hat

phat <- x/n # alternative shortcut: phat <- mean(rolls>=4)

phat[1] 0.395

# 95% confidence interval, using c(-1,1) as a shortcut for ±

phat + c(-1,1) * qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(phat*(1-phat)/n)[1] 0.32725 0.46275Thus, a 95% confidence interval for \(p\), i.e. the true probability of 4 or 5, is (0.33,0.46), or in other words, we are 95% confident the true \(p\) is between 0.33 and 0.46.

If a different level of confidence is desired, simply change the argument to qnorm():

# e.g. for 90% interval, implied alpha=0.10 so we want qnorm of (1-0.1/2)=0.95

phat + c(-1,1) * qnorm(0.95) * sqrt(phat*(1-phat)/n)[1] 0.3381424 0.4518576

# a shortcut is to take the midpoint between the confidence level and 1

# another example, for a 99% interval, we want qnorm of 0.995

phat + c(-1,1) * qnorm(0.995) * sqrt(phat*(1-phat)/n)[1] 0.3059614 0.4840386Note the lower the confidence desired the smaller the interval, and vice versa the higher the confidence desired the larger the interval.

12.1.3 Hypothesis test

For a one-proportion scenario, you wish to test the following hypotheses:

\[ H_0:p~=~p_0~~~~~~~\\ ~~~~~~~~H_a:p~<,\,\ne,\,\text{or}>~p_0 \]

where \(p_0\) is your hypothesized true probability under the null.

You start, as always, by assuming the null, i.e. suppose that \(X\sim\bin(n,p_0)\). Note this means your sample observation \(x\) is drawn from this distribution.

For the p-value, simply compute the appropriate tail area of \(x\) corresponding to the alternative. Remember the rule is for one-sided take the corresponding side tail, and for two-sided take the two outer tails (or take one outer tail and double it).

Then finally, compare with \(\alpha\) and make a conclusion.

Continuing with the die example, we saw in our sample \(\hat p=0.395\) was close to what we expect for a fair die where \(p_0=0.4\). Let’s formally test this. Recall from last chapter if we wish to reject \(H_0\) if our sample statistic is too high OR too low, we choose the two-sided alternative. This applies here, since if \(\hat p\) is too low or too high vs \(0.4\), we should reject. Thus, we choose:

\[ H_0:p=0.4\\ H_a:p\ne0.4 \]

Next, under the null we have \(X\sim\bin(200,0.4)\). This distribution is shown below, along with a red line at our observed sample \(x=79\).

mu = n*.4 ; sd = sqrt(n*.4*(1-.4))

tibble(k=floor(mu-3*sd):ceiling(mu+3*sd),p=dbinom(k,n,0.4)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=k,y=p)) + geom_col() + geom_vline(xintercept=x, color="red", linewidth=1.5) +

ggtitle(str_glue("Distribution of X under null hypothesis, i.e. Bin({n},0.4)"))Recall for a two-sided alternative, we take the “outer-tail” corresponding to our observed statistic and multiply by 2 to get our final p-value. Here, this means we look for \(2\cdot\p(X\le79)\) where \(X\sim\bin(200,0.4)\).

# our two-sided p-value here

2 * pbinom(x, n, 0.4)[1] 0.9463115Important note: if our sample \(x\) were on the RIGHT half of the curve instead of the left, then the “outer-tail” here would be the RIGHT side tail, i.e. \(\p(X\ge x)\).

If instead our alternative had been \(<\) or \(>\), then instead the p-value here would be \(\p(X\le79)\) or \(\p(X\ge79)\) respectively.

# p-value if Ha had been p<0.4

pbinom(x, n, 0.4)[1] 0.4731557

# p-value if Ha had been p>0.4 (note the -1 to include the bar at x)

1 - pbinom(x-1, n, 0.4)[1] 0.5838754In any of these cases, we see the p-value is quite large compared to \(\alpha\). This means our experimental result of \(x=79\) was in fact close to our expectations, so there’s no evidence to refute the null. Thus, we do not reject the null, and we conclude the die appears to be fair.

12.1.4 Approximate Z-test

Alternatively, a normal approximation can also be used—assuming the approximation is valid—resulting in a normal or Z-test for one proportion. Different sources list different conditions, but commonly the approximation is considered valid if you have at least 5 successes and 5 failures in your sample.

Under the null, the sample proportion \(\hat p\) has an approximate normal distribution:

\[ \hat p\asim\n\left(p_0~,\sqrt{p_0(1-p_0)/n}\right) \]

Thus, we can find the corresponding p-value by computing a \(z_\obs\) test statistic:

\[ z_\obs=\frac{\hat p-p_0}{\sqrt{p_0(1-p_0)/n}} \]

then finding the appropriate tail area. For additional accuracy, a continuity correction of \(\pm0.5/n\) can be added/subtracted onto \(\hat p\) depending on the direction of the tail.

12.1.5 R method

Of course, you can also use R to compute the interval or do the testing. This is a good way to check your manual calculations to make sure you did it right. The function for both is binom.test(). It accepts several arguments:

xis the observed sample count \(x\)nis the sample sizenp(defaults to 0.5) is the hypothesized proportion under the null \(p_0\)alternative(defaults to"two.sided") controls the direction of the alternative and can be set instead to either"greater"or"less"conf.level(defaults to 0.95) controls the desired confidence level

Important note: setting a one-sided alternative will generate a one-sided confidence interval with one end at 0 or 1, which is generally not what we desire, so if you want a standard confidence interval as well as a one-sided test, you should run the function twice.

Continuing with the die example, recall we still have x, n defined

[1] 79 200Let’s compute a 95% confidence interval for our problem:

binom.test(x, n, p=0.4)

Exact binomial test

data: x and n

number of successes = 79, number of trials = 200, p-value = 0.9425

alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.4

95 percent confidence interval:

0.3267650 0.4663964

sample estimates:

probability of success

0.395 Note this interval is very slightly wider than our computation, since it uses a modified method called the Clopper-Pearson formula, which is technically slightly better than our method which is called the Wald interval, but this is beyond the scope of STAT240. For our purposes we will prefer the simpler Wald method.

We can also compute a 90% or 99% interval:

binom.test(x, n, p=0.4, conf.level=0.90)

Exact binomial test

data: x and n

number of successes = 79, number of trials = 200, p-value = 0.9425

alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.4

90 percent confidence interval:

0.3371018 0.4552518

sample estimates:

probability of success

0.395

binom.test(x, n, p=0.4, conf.level=0.99)

Exact binomial test

data: x and n

number of successes = 79, number of trials = 200, p-value = 0.9425

alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.4

99 percent confidence interval:

0.3069060 0.4882182

sample estimates:

probability of success

0.395 If you demand an R method for our simpler Wald interval (e.g. to check your own computation), the BinomCI() function from the DescTools package works:

# compute wald interval to check our work

DescTools::BinomCI(x, n, 0.95, method="wald") est lwr.ci upr.ci

[1,] 0.395 0.32725 0.46275For a hypothesis test, note the previous outputs all show that the two-sided p-value is 0.9425. This is once again very slightly different from our computation, since it uses a slightly more exact method where instead of doing \(2\cdot\p(X\le79)\), it computes \(\p(X\le79)+\p(X\ge81)\).

[1] 0.9424936Again, we can feel free to continue doubling the outer tail area on one side as an approximation, which should usually be fairly accurate. We can also run one-sided tests if we wish:

binom.test(x, n, p=0.4, alternative="less")

Exact binomial test

data: x and n

number of successes = 79, number of trials = 200, p-value = 0.4732

alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is less than 0.4

95 percent confidence interval:

0.0000000 0.4552518

sample estimates:

probability of success

0.395

binom.test(x, n, p=0.4, alternative="greater")

Exact binomial test

data: x and n

number of successes = 79, number of trials = 200, p-value = 0.5839

alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is greater than 0.4

95 percent confidence interval:

0.3371018 1.0000000

sample estimates:

probability of success

0.395 This time, the p-values are exactly what we found previously (up to rounding).

12.2 Two proportions

12.2.1 Model notation

In the two-proportions scenario, suppose we draw samples of size \(n_1\), \(n_2\) from two different populations, and we again assume everything is independent (both within and between the two samples). Suppose the populations have true probabilities \(p_1\), \(p_2\) of succeeding for each trial, and again these are treated as true unknown constants.

Then, our models for the true distributions are \(X_1\sim\bin(n_1,p_1)\) and \(X_2\sim\bin(n_2,p_2)\).

Let \(x_1\), \(x_2\) be observed numbers of successes in our samples where \(0\le x_1\le n_1\) and \(0\le x_2\le n_2\) and define \(\hat p_1=x_1/n_1\), \(\hat p_2=x_2/n_2\) as the corresponding proportions of successes in our samples.

Again, we know from the LLN that \(\hat p_1\to p_1\) and \(\hat p_2\to p_2\) so we take \(\hat p_1\), \(\hat p_2\) as our point estimates for \(p_1\), \(p_2\).

So far it’s all pretty intuitive.

Again, let’s see all this in the context of an example. Let’s use this dataset of thoracic surgery outcomes for lung cancer patients from the Wroclaw Thoracic Surgery Centre at the University of Wroclaw. A slightly cleaned version can be found here: thoracic.csv.

# remember to load packages and set any desired options

thoracic <- read_csv("https://bwu62.github.io/stat240-revamp/data/thoracic.csv")

thoracic# A tibble: 470 × 17

dgn fvc fev1 perf pain haem dysp cough weak size type2dm mi6

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <lgl> <lgl> <lgl> <lgl> <lgl> <chr> <lgl> <lgl>

1 DGN2 2.88 2.16 PRZ1 FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE OC14 FALSE FALSE

2 DGN3 3.4 1.88 PRZ0 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE OC12 FALSE FALSE

3 DGN3 2.76 2.08 PRZ1 FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE OC11 FALSE FALSE

4 DGN3 3.68 3.04 PRZ0 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE OC11 FALSE FALSE

5 DGN3 2.44 0.96 PRZ2 FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE OC11 FALSE FALSE

# ℹ 465 more rows

# ℹ 5 more variables: pad <lgl>, smoker <lgl>, asthma <lgl>, age <dbl>,

# survive1 <lgl>There are a lot of columns here we can use (see linked page for explanations of all variables), but just to keep the example simple, suppose we want to see if patients who are smokers have worse 1-year survival rates than non-smokers (spoiler: they do).

Let’s consider population 1 to be non-smokers and population 2 to be smokers. For each population, we can use dplyr to calculate the number of 1-year survivors in each sample (\(x_1\), \(x_2\)) and divide by the total number of smokers and non-smokers (\(n_1\), \(n_2\)) to get the 1-year survival rates for each group (\(\hat p_1\), \(\hat p_2\)).

thoracic_smoker_summary <- thoracic %>%

count(smoker, survive1, name="x") %>%

group_by(smoker) %>%

mutate(n=sum(x)) %>%

summarise(x=last(x), n=last(n), phat=x/n)

thoracic_smoker_summary# A tibble: 2 × 4

smoker x n phat

<lgl> <int> <int> <dbl>

1 FALSE 77 84 0.917

2 TRUE 323 386 0.837We can see now that \(x_1=77\), \(x_2=323\), \(n_1=84\), \(n_2=386\), \(\hat p_1=0.917\), \(\hat p_2=0.837\).

We can now take this dataset and proceed to find a confidence interval or conduct a hypothesis test.

12.2.2 Confidence interval

For a two-proportions scenario, generally our goal is to run inference on the difference of the underlying population probabilities \(p_1-p_2\). We think of this as our parameter of interest.

For this parameter, our point estimate naturally is the difference of our sample proportions \(\hat p_1-\hat p_2\). Then, our interval takes the form:

\[ \text{$C\%$ or $(1\!-\!\alpha)$ interval}~=~(\hat p_1-\hat p_2)~\pm~z_{\alpha/2}\cdot\sqrt{\frac{\hat p_1(1-\hat p_1)}{n_1}+\frac{\hat p_2(1-\hat p_2)}{n_2}},~\text{ where} \]

\(\hat p_1-\hat p_2\) is our point estimate of the true difference \(p_1-p_2\),

\(z_{\alpha/2}\) is the same \(\alpha\)-level normal critical value,

\(\sqrt{\frac{\hat p_1(1-\hat p_1)}{n_1}+\frac{\hat p_2(1-\hat p_2)}{n_2}}\) is the standard error of the difference of our sample proportions, i.e. \(\se(\hat p_1-\hat p_2)\). This formula comes from the fact that for independent \(X\), \(Y\), \(\var(X\pm Y)=\var(X)+\var(Y)\)

Continuing with the thoracic surgery example, let’s compute the 95% confidence interval for the true difference of survival probability \(p_1-p_2\) between smokers and non-smokers

# starting with summary, mutate to add se contribution from each group

# then summarize to get the point estimate, combined se, and interval bounds

# note -diff() is necessary to get row1-row2

thoracic_smoker_summary %>% mutate(se = sqrt(phat*(1-phat)/n)) %>%

summarize(p1mp2 = -diff(phat), se = sqrt(sum(se^2)),

lower95 = p1mp2-1.96*se, upper95 = p1mp2+1.96*se)# A tibble: 1 × 4

p1mp2 se lower95 upper95

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0.0799 0.0355 0.0102 0.150Thus we can see our 95% confidence interval for the true difference in probabilities is (0.010,0.15). In other words, based on the data, we’re 95% confident lung cancer patients who don’t smoke are between 1.0% and 15% more likely to survive for at least 1 year after receiving thoracic surgery than those who do smoke.

12.2.3 Hypothesis test

Again, for a two-proportions scenario, we’re usually interested on inference for the difference of the underlying population probabilities \(p_1-p_2\). For two proportions we must resort to the approximate normal or Z-test, which is typically considered a valid approximation as long as you have at least 5 successes and 5 failures in each sample. The hypotheses are:

\[ H_0:p_1-p_2~=~d~~~~~~~\\ ~~~~~~~~H_a:p_1-p_2~<,\,\ne,\,\text{or}>~d \]

where \(d\) is your hypothesized true difference in the populations’ probabilities under the null. By far the most common case is \(d=0\) which means we end up testing the following:

\[ H_0:p_1~=~p_2~~~~~~~~\\ ~~~~~~~H_a:p_1~<,\,\ne,\,\text{or}>~p_2 \]

For STAT240 we will focus on this \(d=0\) case42, where under the null the two populations have the same probability and any observed differences in sample proportion are due to random chance, and we must compute a “pooled” sample proportion estimate \(\bar p\), since it doesn’t make sense to have two different sample proportion estimates.

\[ \bar p=\frac{x_1+x_2}{n_1+n_2} \]

Then, we compute our \(z_\obs\) test statistic as:

\[ z_\obs=\frac{(\hat p_1-\hat p_2)-0}{\sqrt{\bar p(1-\bar p)\left(\frac1{n_1}+\frac1{n_2}\right)}} \]

Finally, we compute our p-value by taking the appropriate tail area.

Continuing with the thoracic surgery example, where we defined sample 1 as non-smokers and sample 2 as smokers, it makes sense to ask if non-smokers have higher rates of 1-year survival than smokers. Thus, we choose these hypotheses:

\[ H_0:p_1-p_2=0\\ H_a:p_1-p_2>0 \]

or in other words,

\[ H_0:p_1=p_2\\ H_a:p_1>p_2 \]

Then, applying the above formulae, we obtain:

thoracic_smoker_summary %>%

summarise(p1mp2 = -diff(phat), pbar = sum(x)/sum(n),

z = p1mp2/sqrt(pbar*(1-pbar)*sum(1/n)), pval = 1-pnorm(z))# A tibble: 1 × 4

p1mp2 pbar z pval

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0.0799 0.851 1.86 0.0312Our test statistic \(z_\obs=1.86\) gives us an upper-tail p-value of \(0.0312\) which is less than the standard \(\alpha=0.05\), so we can reject the null here.

In summary, at the \(\alpha=0.05\) significance level, the data suggests lung cancer patients who don’t smoke are significantly more likely to survive for at least 1 year after receiving thoracic surgery than those who do smoke.

12.2.4 R method

The R method for analyzing two proportions is prop.test(), unlike binom.test() which can only handle one proportion. The arguments are similar (see help page for details), except for x and n we input a vector of success counts and sample sizes corresponding to our two samples. Note the alternative, if one-sided, indicates if the first sample is less/greater than the second sample.

Note the print-out of prop.test() actually references a \(\chi^2\)-test instead of a normal-based test, but they are equivalent formulations of the same methodology and will produce the exact same intervals and p-values, as we’ll see in the example below.

Continuing with the thoracic surgery example, recall our sample statistics:

thoracic_smoker_summary# A tibble: 2 × 4

smoker x n phat

<lgl> <int> <int> <dbl>

1 FALSE 77 84 0.917

2 TRUE 323 386 0.837For both interval and testing approaches, we must give the x and n columns to prop.test(). The other arguments depend on exactly what we wish to do.

To compute a proper 95% confidence interval for the true probability difference, we must always use the default two-sided alternative:

2-sample test for equality of proportions with continuity correction

data: th$x out of th$n

X-squared = 2.8711, df = 1, p-value = 0.09018

alternative hypothesis: two.sided

95 percent confidence interval:

0.002970985 0.156787219

sample estimates:

prop 1 prop 2

0.9166667 0.8367876 Note by default this also applies a continuity correction, which is generally recommended, where the interval is slightly widened by adjusting both upper and lower bounds by \(\pm0.5(1/n_1\!+\!1/n_2)\). We can verify this with a quick modification to our earlier computation:

thoracic_smoker_summary %>% mutate(se = sqrt(phat*(1-phat)/n)) %>%

summarize(p1mp2 = -diff(phat), se = sqrt(sum(se^2)),

lower95 = p1mp2-1.96*se, upper95 = p1mp2+1.96*se,

lower95_cor = lower95-0.5*sum(1/n), upper95_cor = upper95+0.5*sum(1/n))# A tibble: 1 × 6

p1mp2 se lower95 upper95 lower95_cor upper95_cor

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0.0799 0.0355 0.0102 0.150 0.00297 0.157To forgo the continuity correction, simply add the argument correct = FALSE.

2-sample test for equality of proportions without continuity correction

data: th$x out of th$n

X-squared = 3.4727, df = 1, p-value = 0.06239

alternative hypothesis: two.sided

95 percent confidence interval:

0.0102187 0.1495395

sample estimates:

prop 1 prop 2

0.9166667 0.8367876 To run a hypothesis instead, we must remember to set the correct alternative hypothesis direction. Here we want "greater" since group 1 is non-smokers, which we believe should have greater survival probability than non-smokers which are group 2.

2-sample test for equality of proportions with continuity correction

data: th$x out of th$n

X-squared = 2.8711, df = 1, p-value = 0.04509

alternative hypothesis: greater

95 percent confidence interval:

0.01417053 1.00000000

sample estimates:

prop 1 prop 2

0.9166667 0.8367876 Again, this includes by default the continuity correction, which is applied by \(\pm0.5(1/n_1\!+\!1/n_2)\) onto \((\hat p_1\!-\!\hat p_2)\) such that the absolute value is lowered in the \(z_\obs\) equation, effectively slightly “shrinking” the observed difference in sample proportions. We can also verify this with a quick modification to our earlier computation:

thoracic_smoker_summary %>%

summarise(p1mp2 = -diff(phat), pbar = sum(x)/sum(n),

z = p1mp2/sqrt(pbar*(1-pbar)*sum(1/n)), pval = 1-pnorm(z),

z_cor = (p1mp2-sign(p1mp2)*0.5*sum(1/n))/sqrt(pbar*(1-pbar)*sum(1/n)),

pval_cor = 1-pnorm(z_cor))# A tibble: 1 × 6

p1mp2 pbar z pval z_cor pval_cor

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0.0799 0.851 1.86 0.0312 1.69 0.0451Again, if this is not desired, turn it off with correct = FALSE

2-sample test for equality of proportions without continuity correction

data: th$x out of th$n

X-squared = 3.4727, df = 1, p-value = 0.03119

alternative hypothesis: greater

95 percent confidence interval:

0.02141825 1.00000000

sample estimates:

prop 1 prop 2

0.9166667 0.8367876 In either case, we can see everything matches perfectly and we are content.